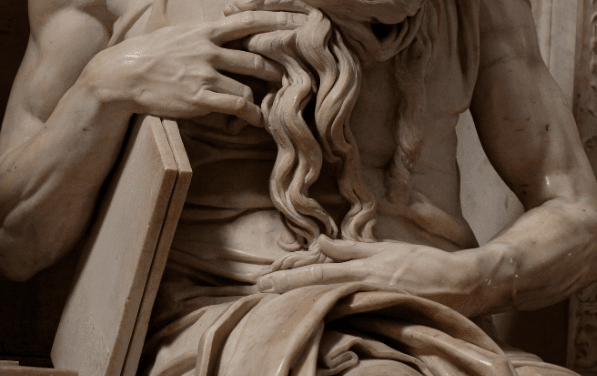

But computer science majors keep launching startups that are technology- rather than people-centered. For example, in San Francisco (where else!) two restaurants opened in the last few years. Eatsa had fully automated ordering and service while human chefs prepared the food out back. Creator automated the food creation, but staffed the restaurant with friendly greeters to create what they call “an intimate, social, human-interaction-rich service experience.” Both are using automation to cut the cost of serving food, but only one of them has realized that we go out to eat – rather than ordering in – because we sometimes like to be with other people. You might be surprised to hear me calling for more humanities education, rather than Python classes, as a response to the increasing sophistication of machine learning. I’m no luddite. I’ve spent my life working in tech – initially delivering complex projects for huge corporations and, later on, creating a digital marketing business using some of the smartest tools available. But while I admire great engineers, I always remember that technology is a tool. To take an extreme example, the people who made Michelangelo’s chisel or Leonardo’s brushes were undoubtedly the finest craftspeople of their age. That chisel was essential, but when I look at the tendons and veins in the sculpture’s arms, I feel the strength of the man depicted in front of me. When is see the delicate details of his fingers, I feel the fragility and tenderness of what it is to be human. When I see the folds of the robe or the fall of his beard, I don’t just marvel at the sharpness of Michelangelo’s chisel. Instead I feel a human connection with Moses not as myth, not as marble, but as a man. This connection is something that even the most sophisticated AI tools just can’t replicate. Sure, there are generative neural networks that can create new pictures, write new music, and edit together new film trailers. But not one of them knows what it is to be moved, or how to move someone. The beauty in Michelangelo’s sculpture is in what he chose to emphasize, what he chose to omit, Michelangelo made these deliberate choices in order to inspire awe, to evoke wonder. Awe and wonder are feelings that no machine has – yet – been able to experience. But they’re the stock-in-trade of artists and storytellers. We’re only just starting to understand what happens in the brain when we encounter a moving work of art. In the last decade, neuroscientists and psychologists have started using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) – a type of scan that reveals the brain at work – to see what happens when we see a painting, listen to music, or read a story. The emotional cascades are complex, distinctive, and extremely personal to each of us. And yet every time we make someone laugh or arouse their pity we touch their minds and set off these same cascades. That is what it means to make a human connection. In theory, we could try to train neural networks to generate works that provoke these same patterns of brain activation. But when someone tells you a story, takes a picture, or sings a song, it’s an act of communication as much as creation. Creativity happens because we have something we want to share. As humans, we all need “intimate, social, human-interaction-rich experiences.” And not just when buying a burger. I run a digital marketing organization and – while we obviously care about SEO, Google Map rankings, dwell times, and bounces as much as anyone – I know that all these technologies and metrics are just the means to an end. Our clients are only interested in ranks or clicks if they’re result in a connection. Years of experience taught me that a great (and truthful) story is more persuasive, more moving, than any amount of data. Professor Magdalena Wojcieszak of the University of Amsterdam has recently done research that shows just how right that intuition is. Her research team showed people personal stories from undocumented immigrants (“I have been working hard. Multiple jobs, long hours. My employers are always happy with me and I have been paying all my taxes.”) and also showed statistical data (“Regularizing the migration status of undocumented migrants would add $1.5 trillion to the economy… Eighteen percent of small businesses are owned by migrants.”) People said they found the statistical data more persuasive. But when they were asked questions about their attitudes towards undocumented migrants, those participants who had read the stories had become much more sympathetic to, and much more likely to support the cause of, migrants to the United States, than those who had been given the numerical data. We believe that we’re entirely rational, but as a species we’re far more social than we are scientific. The upside of this is that we can use the power of connection for good. Persuasive stories have been used to help people follow healthier lifestyles, stay in school longer, even cut down on drinking alcohol. And stories stay with people. One recent study showed that stories change people’s minds instantly but the impact of that story continues to grow over the next two weeks. When we tell (and hear) stories, our understanding of each other grows. We need more, not fewer, experts in the human condition in the coming years. I’m not arguing that we need fewer computer science majors. I’m not suggesting that you quit your Python course and take stand up comedy instead. But whether you choose to call it augmented intelligence, assistive intelligence, intelligent automation, or something else, never forget the nearly eight billion real humans you share a planet with. They have far more in common with you than any machine ever will.